Peer-Reviewed Articles

Below you will find abstracts for peer-reviewed articles I have recently published. Several are open-access, and I am also happy to pass along pre-prints upon request.

I also have several articles in the pipeline. If you are interested in any of these topics and would like to read an early draft, please contact me by email at arthurobst03@gmail[dot]com.

A paper providing a conceptually crisp definition of wilderness and establishing its enduring relevance in a world of accelerating ecological disruption.

A paper scrutinizing the ethics of recent outdoor geoengineering experiments.

A paper on the conceptual foundations and forward-looking prospects of the U.S. ‘National Wild and Scenic River System.’

A co-authored paper evaluating the public-health impacts of solar geoengineering and their ethical implications.

Beware the Toll Dodgers: Defending the Tollgate Principles for Governing Solar Geoengineering Climatic Change 179, 17 (2026) with Stephen M Gardiner https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-025-04060-w

The Tollgate Principles (‘TGPs’) aim to represent ‘the price that must be paid’ by anyone claiming to be ethically serious about pursuing solar geoengineering (Gardiner and Fragnière, Ethic Policy Environ 221(2):143–174, 2018). The TGPs are influential but, like other governance principles, have also provoked criticism. This paper clarifies the Tollgate approach by responding to objections and dissolving some perceived tensions. It argues that, while not the final word, the TGPs are an important step in the evolution of geoengineering governance and should continue to be taken seriously at all levels. It concludes that rather than “beware the Toll Keepers” (Briggle, Ethic Policy Environ 21(2):187–189, 2018) we should instead “beware the Toll Dodgers”: those who would brush aside the TGPs and other ethics-centered approaches. As well as defending the Tollgate approach specifically, the discussion provides broader lessons for governing geoengineering and other controversial technological interventions.

What Would Aldo Leopold Think About Geoengineering? Climatic Change 179, 5 (2026) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-025-04099-9

Corresponding with the accelerating crises of climate and biodiversity loss has been a call in contemporary environmentalism to think and act at planetary scales to address a planetary problem. One prominent proposal, stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), would attempt to replicate the cooling effect of volcanic eruptions by tactically injecting reflective particles into the atmosphere in an attempt to reverse global warming. This article first constructs a new case for SAI on behalf of the wild, an idea that has appeared in passing within several influential arguments for solar engineering but has not received widespread endorsement. I then introduce the reader to Aldo Leopold’s land ethic and defend one interpretation that is supported by mainstream interpreters in the literature, drawing the reader’s attention to the important role that a human/nature parallel plays in Leopold’s moral reasoning and the value he places on preserving biodiversity. Then, I apply this framework to SAI and argue that it poses an intractable dilemma for ‘geoengineering for the wild.’ I provide a novel reading of Leopold’s famous essay “Thinking Like a Mountain” and argue it illustrates the importance of two distinct forms of intellectual humility in his thought. Then, I present the dilemma. It appears when one answers a simple question: is it better for SAI to “work” or “fail?” As I will discuss, this question is too simple, but it is revealing. I will argue in what follows that from a Leopoldian outlook both success and failure in solar geoengineering should deeply trouble us. This constitutes 'the climate engineer's dilemma.'

Wilderness Values in Rewilding: Transatlantic Perspectives. Environmental Values 34, 3 (2025) with Linde De Vroey https://doi.org/10.1177/09632719241305719

This article re-investigates the underlying values driving the rapidly growing rewilding movement in Europe and North America. In doing so, we respond to a common academic narrative that draws a sharp distinction between North American and European approaches to rewilding. Whereas the first is said to promote a colonial vision of wilderness, European rewilding is claimed to value a more inclusive notion of wildness. We challenge this narrative through a genealogical investigation into the wild(er)ness ideas that inspired rewilding, showing that North American and European rewilding draw from similar philosophical sources with cross-continental origins. Thus, we contend that a linguistic shift from ‘wilderness’ to ‘wildness’ fails to engage substantively with the colonial critique it alleges to resolve. Through two case studies, we show how both wilderness and wildness concepts have been employed to support either colonialism or decolonial resistance and draw attention to the need to consider specific socio-political contexts when assessing rewilding. Ultimately, we propose that reclaiming a liberatory meaning of wild(er)ness, articulated in a critical tradition of wild(er)ness advocacy, will be an essential step in decolonising rewilding.

Moral Reasoning in the Climate Crisis: A Personal Guide Moral Philosophy & Politics 11, 2 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1515/mopp-2023-0076

This article substantiates the common intuition that it is wrong to contribute to dangerous climate change for no significant reason. To advance this claim, I first propose a basic principle that one has the moral obligation to act in accordance with the weight of moral reasons. I further claim that there are significant moral reasons for individuals not to emit greenhouse gases, as many other climate ethicists have already argued. Then, I assert that there are often no significant moral (or excusing) reasons to emit greenhouse gases. In any such trivial-cost— but not necessarily trivial-impact— cases, the individual then has an obligation to refrain. Finally, I apply the Moral Weighing Principle to everyday situations of emitting and establish two surprisingly substantial implications: the relevance of virtues to the interpersonal assessment of environmentally harmful actions, and the extensive individual ethical obligations that exist short of purity.

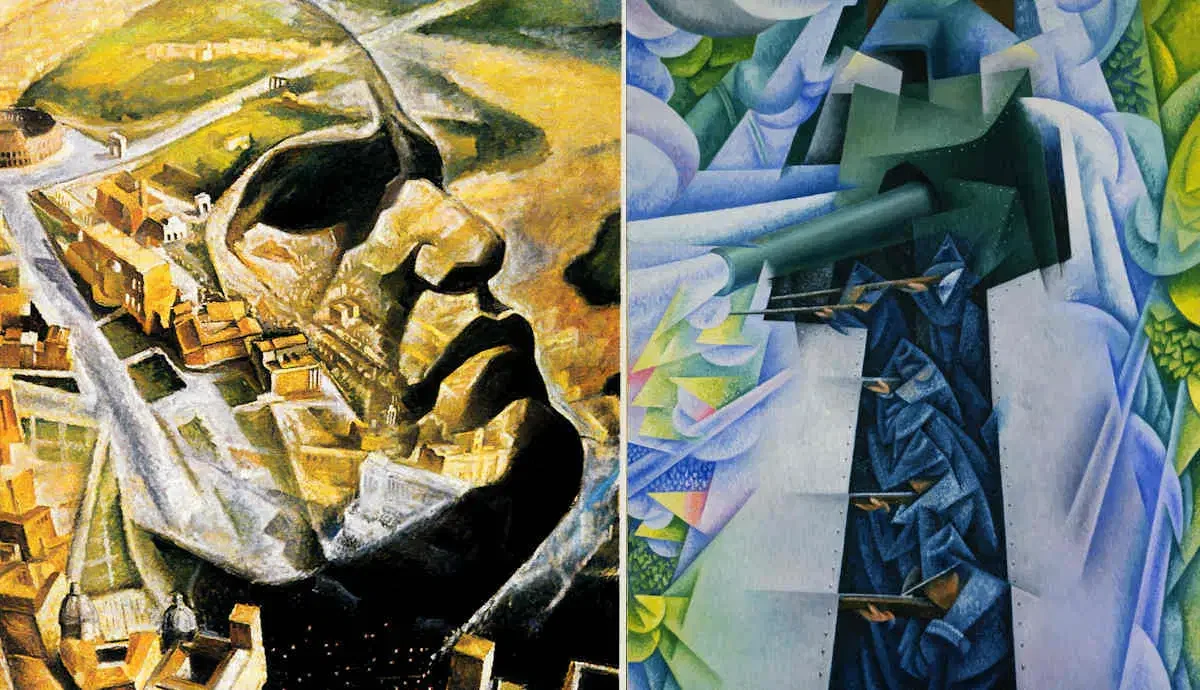

Flying from History, Too Close to the Sun: The Anxious, Jubilant Futurism of ‘Age of Man’ Environmentalism. Environmental Ethics 45, 4 (2023) https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics202383065

There is a remarkable trend in contemporary environmentalism that emphasizes ‘accepting responsibility’ for the natural world in contrast to outdated preservationist thinking that shirks such responsibility. This approach is often explained and justified by reference to the Anthropocene: this fundamentally new epoch— defined by human domination— requires active human intervention to avert planetary catastrophe. However, in this paper, I turn such thinking on its head. The often jubilant, sometimes anxious, yearning for unprecedented human innovation and— ultimately— control in our new millennia mirrors the Futurist movement that took off near the beginning of the last century. Despite the significant differences in the details of how academics have defended this 21st century environmental outlook, they all represent the true flight from history; they too quickly jettison the ideas of historical environmentalists and so misunderstand the environmental values at the heart of preservation that are more salient than ever.

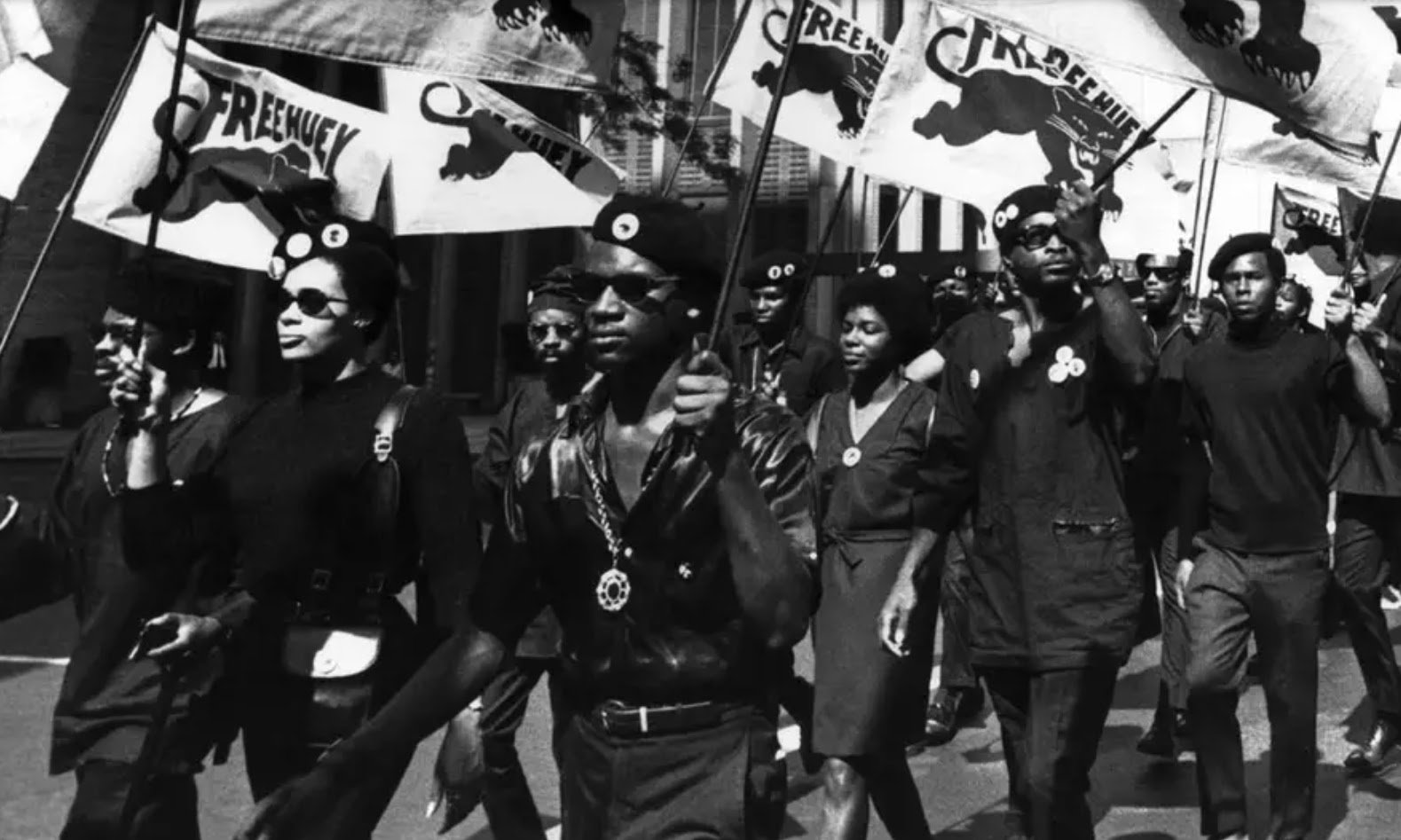

Individual Responsibility and the Ethics of Hoping for a More Just Climate Future. Environmental Values 32, 3 (2023) with Cody C. Dout. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327122X16569260361823

Many have begun to despair that climate justice will prevail even in a minimal form. The affective dimensions of such despair, we suggest, threaten to make climate action appear too demanding. Thus, despair constitutes a moral challenge to individual climate action that has not yet received adequate attention. In response, we defend a duty to act in hope for a more just (climate) future. However, as we see it, this duty falls differentially upon the shoulders of more and less advantaged agents in society. From arguments by Black thinkers like Derrick Bell, we draw a set of distinctions between two types of hope: one for ideal justice, and one for more modest change; and between two types of hopeful actions, those undertaken through formal political channels and those we call ‘extra-political’ actions; and between two sites of differential moral burdens, those of the privileged and those of the oppressed. Ours’ is a case for facing even bleak realities, demanding otherwise, and acting in hope to achieve a better future.